Effects of Trauma

Trauma is defined as an event or situation that overwhelms someone’s ability to cope and leaves that person fearing (real or perceived) death, annihilation or mutilation. The individual may feel emotionally, cognitively and physically overwhelmed. The circumstances of the event commonly include abuse of power, betrayal of trust, entrapment, helplessness, pain, confusion, or loss.

The key to this definition is the word perceived. This is why two people can experience the same situation but have two different responses. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Volume (DSM-5) has quantified the criteria for diagnosing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in children six years of age and younger and persons over the age of six. This diagnosis of PTSD in young children is new to the DSM-5.

For children six and younger, the DSM-5 lists some possible traumatic experiences, including abuse, witnessing interpersonal or community violence, motor vehicle accidents, natural disasters, dog bites and medical procedures. According to the National Center for PTSD, several risk factors for developing PTSD have been identified and include female gender, previous trauma exposure, previous psychiatric disorders, parental psychopathology and lack of support.

Since young children lack the verbal skills to express their trauma, behaviors are used to make a diagnosis. The National Center for PTSD and the DSM-5 have identified some of them. Time skew is one of the behaviors. This is when the child incorrectly sequences trauma-related events. Some children develop an omen formation where they believe signs predicted the event, and if they remain vigilant they can prevent another traumatic event from happening. Other identified behaviors are fear, anxiety, depression, anger and hostility, aggression, sexually inappropriate behavior, self-destructive behavior, feelings of isolation and stigma, poor self-esteem, difficulty trusting others, sexual mal-adaptation and substance abuse. Additional behaviors are relationship problems with family and peers, school problems and acting out behaviors.

Traumatic experiences, especially in utero and in early childhood, have a profound impact on brain development. There are three major divisions of the brain: the brain stem or the reptilian brain, the mid brain or the limbic system, and the neo cortex. The brain is also divided into right and left halves or hemispheres. If a pregnant woman experiences stress, the fetus is exposed to cortisol, a stress hormone. The more prolonged or intense the stress, the greater the amount of cortisol to which the fetus is exposed. This exposure may pre-dispose an infant to being more stressed or more tempermental, to having a smaller window of tolerance. This exposure may possibly cause cognitive delays.

At birth, the right hemisphere of the brain, the emotional and artistic side, is developed. It is intuitive and transitions between seemingly random tasks. Trauma that occurrs before 18 months stunts the development of the right brain and its functional abilities. A traumatic experience during the first 18 months of life can result in behaviors such as: focusing on the minutae, not being able to read and understand facial cues and an inability to make smooth transitions. The left hemisphere of the brain does not begin to come online until 18 months of age. The left brain is the analytical, sequential, logical side. Trauma that occurs after 18 months of age stunts the development of both the left and right hemispheres.

Paul McLean, one of the pioneers of neuroscience, proposed the concept of the triune brain, a brain of three major sections. These sections are the brain stem, the limbic system and the neocortex. The brain stem, also known as the reptilian brain, regulates such things as body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and breathing. The limbic brain regulates emotion, appetite and satiety, including sexual behavior. The neocortex is where the highest brain functions take place– thinking, planning and problem solving. For the sake of understanding trauma, the triune model is the best.

Trauma’s biggest impact is on the limbic system. The amygdala and the hippocampus, two parts of the limbic system, are most impacted. The amygdala is the threat-perception region of the brain. Within milliseconds, the amygdala assesses the environment and determines if it is safe or unsafe. When the amygdala becomes over-stimulated or overactive as a result of a traumatic experience, it can perceive danger where none actually exists. The amygdala can continue in this hyper-vigilant state, impacting cognitive development and causing problems in school. The hippocampus is responsible for converting short-term memory into long-term memory. It “time stamps” an event, giving it a time and place in memory. During a traumatic event, the hippocampus does not work, so the event remains in short-term memory where it is easily accessible. In addition, because the memory has not been “time stamped,” the person feels as if the event is actually happening in the present. The amygdala and the hippocampus combine to make the trauma sufferer believe the trauma is real in the here and now and the person reacts as if it were real.

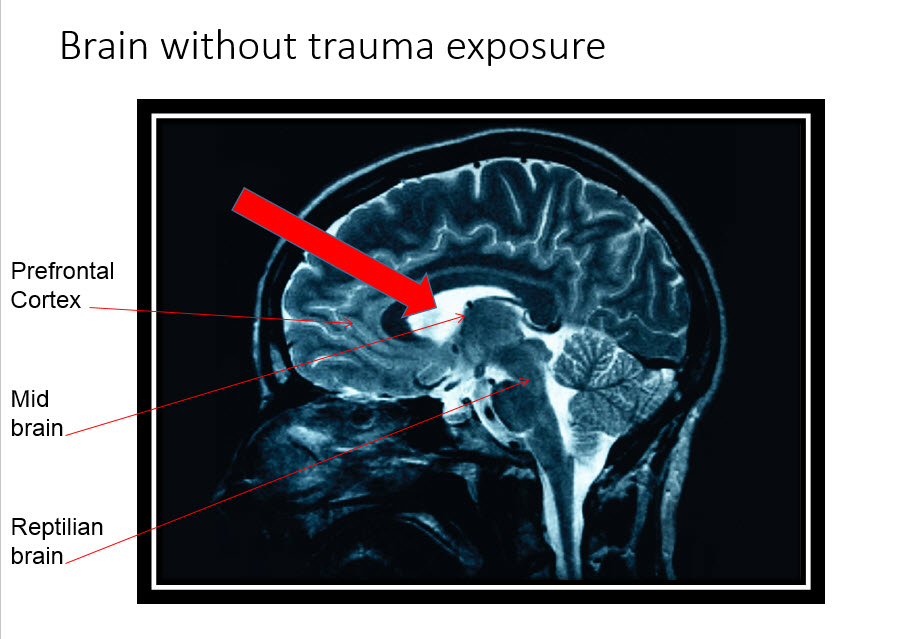

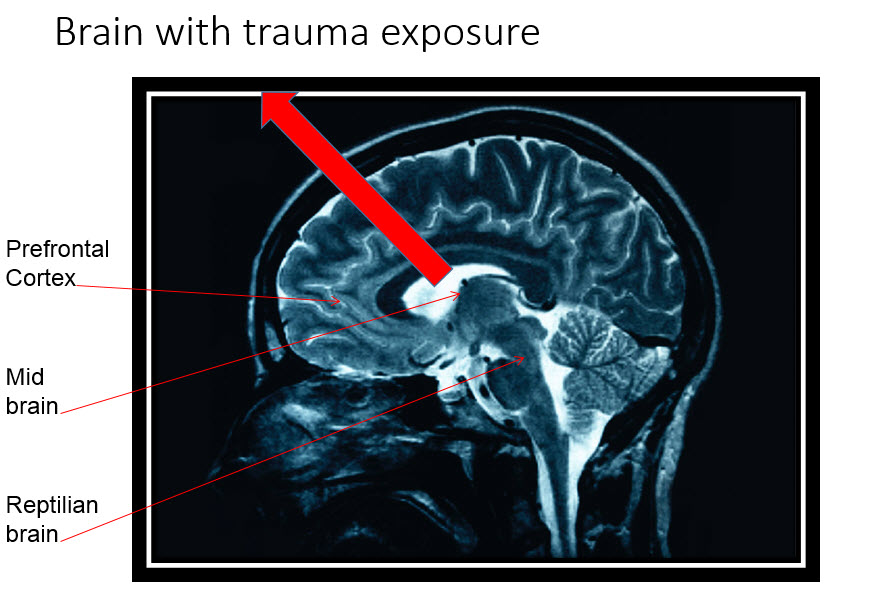

A brain that was not exposed to trauma processes incoming information and responds to that information with “top down” processing. The neo-cortical area, including the pre-frontal cortex, is in control. Decisions and actions are processed through the area of the brain responsible for thinking, planning and problem solving. When a brain is exposed to trauma, that processing becomes “bottom up.” The limbic system controls both the assessment of the information and the response. If the child becomes stressed enough, the reptilian brain processes and responds to the information, and everything is filtered through the lens of survival. The more aroused (stressed) a child is, the lower in the brain the child is.  Children with a trauma history are frequently diagnosed with conditions that address the behavior but not the root cause of the behavior. The trauma survivor can exhibit symptoms of both hyper-arousal and hypo-arousal. Some of these diagnoses include: major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, intermittent explosive disorder and conduct disorder.

Children with a trauma history are frequently diagnosed with conditions that address the behavior but not the root cause of the behavior. The trauma survivor can exhibit symptoms of both hyper-arousal and hypo-arousal. Some of these diagnoses include: major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, intermittent explosive disorder and conduct disorder.

When a person experiences trauma, the adrenaline system kicks in, and one of three responses occur: fight, flight or freeze. When a child has experienced a trauma, that fight-flight-freeze response continues to unconsciously impact the behavior in the present. The child whose reaction during the traumatic experience was a fight response can exhibit symptoms of aggression after the experience. This can result in diagnoses of Intermittent Explosive Disorder and Conduct Disorder, depending on the exact behaviors. The child whose reaction during the traumatic experience was a flight experience can exhibit symptoms of hyperactivity or running away after the experience. This can result in a diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, depending on the actual behaviors. The child whose reaction during the traumatic experience was a freeze response can exhibit symptoms of defiance, daydreaming and shutting down. This can result in a diagnosis of Oppositional Defiant Disorder, depending on the specific behaviors. This past freeze response can also lead to a child who is chronically hypo-aroused, where a child appears to be unaffected by the past trauma, but is in reality every bit as affected as the child who acts out.  Stress, whether real or perceived, triggers the trauma response. In many cases, the response appears to be disproportional to the precipitating event. This is because the precipitating event triggered a “danger alert” in the amygdala. Something about the event reminded the amygdala and the hippocampus of something from the past trauma, and the amygdala responded in survival mode. While the precipitating event was very likely non-threatening, the limbic system did not interpret it as such but instead demanded that all instincts prepare to survive the danger. This is why the response to a request can lead to a reaction that is above and beyond what is considered typical in a child who does not have a trauma history.

Stress, whether real or perceived, triggers the trauma response. In many cases, the response appears to be disproportional to the precipitating event. This is because the precipitating event triggered a “danger alert” in the amygdala. Something about the event reminded the amygdala and the hippocampus of something from the past trauma, and the amygdala responded in survival mode. While the precipitating event was very likely non-threatening, the limbic system did not interpret it as such but instead demanded that all instincts prepare to survive the danger. This is why the response to a request can lead to a reaction that is above and beyond what is considered typical in a child who does not have a trauma history.

Dr. Bruce Perry uses a chart to illustrate how trauma or fear changes thinking, feeling and behaving. For children who have not experienced trauma, they spend most of their time in the calm state or the aroused state. When they do move along the continuum, they typically move from alarm to fear to terror with a pattern that is predictable to their caregivers. When a child has experienced a trauma, there is no “typical” progression from calm to terror. With no provocation that makes sense to the caregiver, a child who has experienced trauma can go very quickly from a calm state or an aroused state straight to terror. As dysregulation increases, the child regresses developmentally. When a child is in a state of terror, he or she is in a part of the brain often referred to as the reptilian brain. The only thing that matters at that point is survival, and the child will do anything to survive. Because this need for survival is in response to past events, the actions are out of proportion to the present. The child has lost his sense of time.

Dr. Perry discusses two continuums, or paths, that trauma responses can take. One is the dissociative continuum. This is the freeze response of the fight-flight-freeze response and is typical of females and younger children. That does not mean that older youth or males do not exhibit behaviors on the dissociative continuum. The other path is the hyperarousal continuum, the fight and flight response of the fight-flight-freeze response. This response is typical of males and older youth but does not mean that younger children and females will not exhibit behaviors on this continuum.

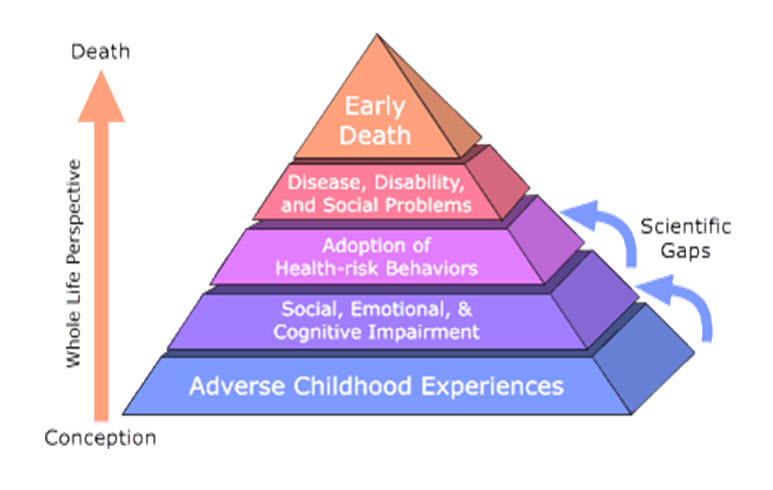

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study conducted by the Center for Disease Control documented additional experiences resulting from childhood traumatic experiences. Approximately 17,000 participants were questioned over the course of two years from 1995 to 1997. The study findings suggest that certain childhood experiences lead to illness (mental and physical), poor life quality and early death. This appears to happen because the adverse childhood experiences lead to the prevalence and development of habits that lead to poor outcomes. The pyramid below represents the Center for Disease Control’s representation of the “whole life” nature of their study.  The ACE study defined the experiences as follows:

The ACE study defined the experiences as follows:

- Abuse

- Emotional abuse

- Physical abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Neglect

- Emotional abuse

- Physical abuse

- Household Dysfunction

- Mother treated violently

- Household substance abuse

- Household mental illness

- Parental separation or divorce

- Incarcerated household member

The ACE study assesses the amount of childhood stress. The risk for the following health problems is proportional to the amount of stress.

- Alcoholism and alcohol abuse

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Depression

- Fetal death

- Health-related quality of life

- Illicit drug use

- Ischemic heart disease

- Liver disease

- Risk for intimate partner violence

- Multiple sexual partners

- Sexually transmitted diseases

- Smoking

- Suicide attempts

- Unintended pregnancies

- Early initiation of smoking

- Early initiation of sexual activity

- Adolescent pregnancy

All of the neurobiological information and the longitudinal studies point to one thing. Childhood trauma has a significant impact on all aspects of a child’s life. Ways of interacting with children with a traumatic history can mitigate the adverse consequences. It is important to remember that as the child regresses, the area of the brain that is in charge of the behavior moves in a top-down progression. While in the calm state and the aroused state, the neocortex and the cortex, the thinking portions of the brain, are in charge. Once the child moves to the alarm state, the limbic system, the emotional portion of the brain, is in charge. Once the brain moves to this area, a child cannot access the neocortex and the cortex. He or she is no longer capable of abstract or concrete thought. As the child moves into fear or terror, the midbrain and the brainstem take control, and the child is not capable of abstract or concrete thought or emotion. The time to talk with a child is when they are in the states of calm or arousal. The arousal state is ideal as people learn best and are most receptive when in that state.

People who work with or parent children with trauma histories need to understand that the traumatic event changes how the brain functions. This change results in behaviors that are different than the behaviors of neuro-typical children. Those working with children with a trauma history need to use different techniques and strategies to help the brain heal and to help decrease the behaviors.